A loved one’s dementia diagnosis leaves you reeling, even when it merely confirms your suspicions. You wonder what to do next. Where do caregivers go to find help moving forward?

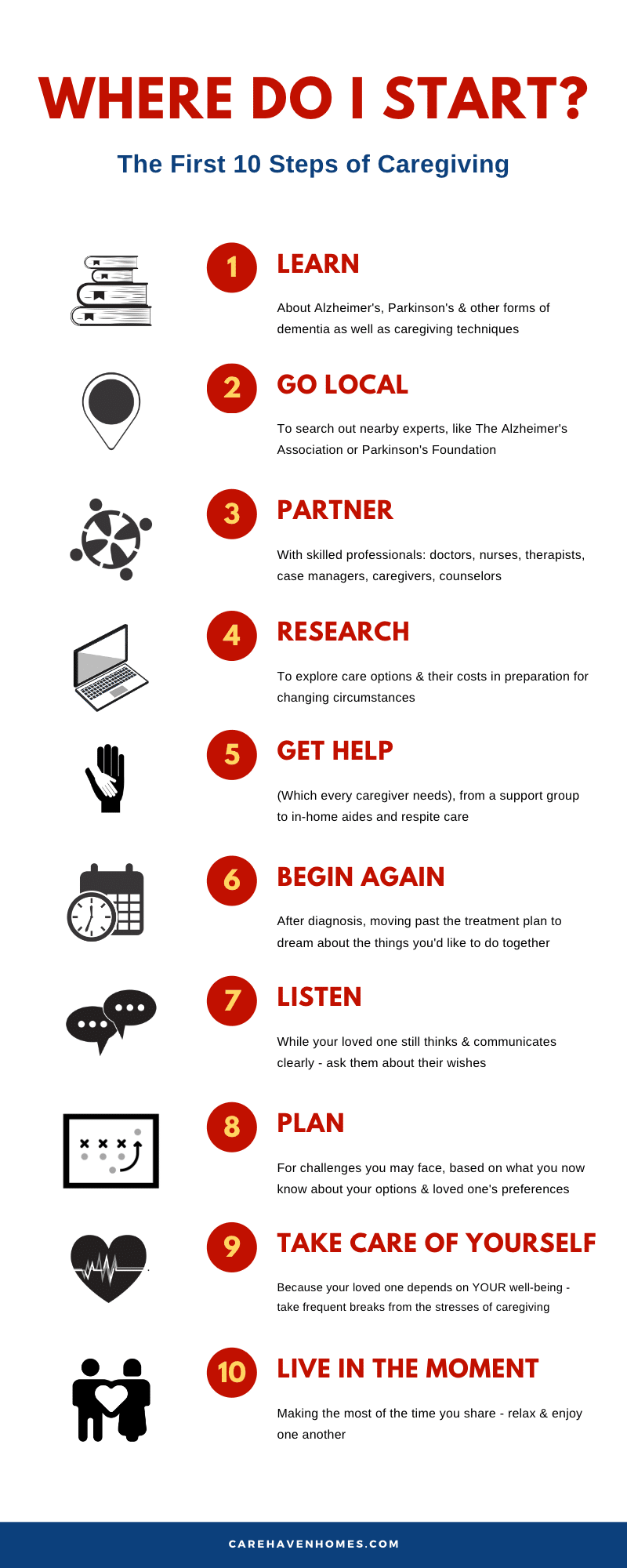

Right here! We’ve mapped your next ten steps. Check out the infographic, then scroll down for more advice on learning, partnering and planning.

Help for family caregivers

Like many team sports, memory care relies on the skills of three squads: offense, defense and special teams.

- While research offensives against Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other memory disorders are making significant strides, they haven’t yet scored cures.

- Meanwhile, our intrepid defenders keep beefing up the playbook with innovative treatments to block dementia’s progress.

- For now, though, people with dementia rely on the heroic efforts of their special teams: the care teams of doctors, nurses and other professionals who provide comforting care.

Today’s best memory care is “small ball.” Every brief interaction filled with kindness and dignity is a big win for someone with dementia. So, surround your loved one with empathetic caregivers. They’re counting on you to be their devoted talent scout.

Below are some of the positions you may need on your care team. (Don’t miss the list of valuable online links in “Training Camp!”)

General manager

Are you cheering in the stands or pacing the sideline?

A piece of advice before we start. If you

- Suspect your loved one has a form of dementia,

- Worry that illness may prevent them from understanding or acting on information their doctors provide or

- Are concerned they can’t convey their wishes regarding treatment,

then be sure you have the legal authority to act on their behalf.

How HIPPA impacts caregivers looking for help

The policies your loved one’s health providers put in place to comply with The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) may prevent you from receiving medical information about your loved one without their consent. Whether you’re a good friend, partner, spouse, parent or adult child won’t matter. Most health providers won’t share information without your loved one’s permission.

HIPPA permits providers limited discretion to disclose a patient’s medical information when in the patient’s best interest. HOWEVER, most doctors rely solely on their patients’ written waivers to avoid potential disputes and hefty penalties.

So, if you oversee your loved one’s care, be sure you have permission to manage their team.

At first, your loved one may resist. Perhaps they’re embarrassed by or afraid of what a future with dementia will bring. Or, if your loved one disagrees with their doctor’s findings, skepticism and suspicion may stand in your way. In any case, it’s not unusual for people to fiercely defend the right to control their destiny.

So, it’s wise to proceed with caution and empathy.

Follow your loved one’s lead

- Start by asking what the doctor said and how your loved one feels about it. You’ll have questions, of course, but wait to ask them. Your first job is to listen and show you care.

- Keep offering help and companionship, a critical role of caregivers. Begin with something simple, like driving your loved one to appointments.

- Eventually, ask to sit in on appointments as well. Quietly take notes. You’re creating a vital record for your family and care team. You’re also learning what care your loved one wants, so you’re prepared to speak for them when they can’t.

- Most providers prefer that patients use the HIPPA waiver forms they’ve customized for their practice. Ask your loved one to complete them as you wait for appointments.

- Initially, focus on building trust with your loved one and others on their care team. Let them manage what they can.

- Volunteer for errands, picking up prescriptions, x-rays or medical equipment with your loved one’s permission. This gives you the chance to meet even more members of the team.

Get it in writing

If circumstances permit, see that your loved one puts an advance directive in place. In it, they’ll document their preferences regarding treatment and care, including end-of-life wishes. If your loved one already has a Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care or a Living Will, check that it was created or amended after 2003. Any advance directive also should contain HIPPA-compliant language expressly permitting your loved one’s care providers to discuss health information with you. If it doesn’t, suggest it be updated.

About legal capacity

There’s no time like the present. In other words, the time for your loved one to put their affairs in order is shortly after receiving a dementia diagnosis. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, “a person living in the early stage [of dementia] is able to understand the meaning and importance of a given legal document, which means he or she likely has the legal capacity (the ability to understand the consequences of his or her actions) to execute it.”

- The mental capacity required to execute documents legally varies by the document type. A good lawyer, particularly an elder care attorney, can explain these nuances.

- A lawyer also can help your loved one document their wishes, carefully walking them through an advanced directive, will or real estate contract and establishing whether they demonstrate the required capacity.

- Be careful about using free forms you find online, especially if disagreements among family members, friends or other potential beneficiaries may arise.

If your loved one insists on going it alone, ignoring the consequences of their actions, you could go to court. You would have to ask that your loved one be declared legally incapacitated and then request to be named their legal guardian. This is a lengthy, costly and sometimes heated process with an outcome you can’t predict, so consider it only as a last resort.

Training camp

Prepare to care

In order to support your loved one — and work effectively with their care team — you’ll want to learn about Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or any other form of dementia that affects them.

Fortunately, today’s caregivers can easily access help online and in local libraries, bookstores, seminars or support groups.

We recommend the following links:

- NIH National Institute on Aging: Health Information

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging

- Mayo Clinic: Dementia

- The Alzheimer’s Association

- University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center

- Lewy Body Dementia Association

- Parkinson’s Foundation

- The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research

Coaches

Your doctors

Your loved one’s primary care doctor leads the care team. If you’re lucky, they’ve trained as a geriatrician, an expert at treating diseases and conditions common among older adults. These specialists generally are adept at recognizing dementia and determining its cause.

However, it’s more likely you’re working with a primary care physician (PCP) who treats adults of all ages in a family or internal medicine practice. Perhaps your loved one chose them decades ago, impressed at their dogged pursuit of treatments and cures. If so, remember that your loved one’s medical needs are changing. Tread lightly but quietly evaluate whether the PCP can arrive at a diagnosis and suggest a care plan.

If you sense they can’t, then it’s time for a referral. Most PCPs are relieved when tactfully asked for one. In fact, according to The Alzheimer’s Association’s 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures,

- 97% of primary care physicians (PCPs) report waiting for patients to talk about symptoms or request an assessment — 98% count on family members to raise the red flag

- PCPs report not having enough time during routine visits to perform thorough cognitive evaluations and admit they’re not comfortable with current assessment tools

- 99% of PCPs refer patients to specialists when they detect cognitive impairment, usually neurologists or geriatricians — and more than half believe there’s a shortage of such specialists

The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that when you work with a skilled doctor, they can diagnose Alzheimer’s disease with more than 90% accuracy. Find one you and your loved one trust — who answers your questions with confidence, clarity and compassion.

Neurologists

Neurologists specialize in treating diseases and disorders of the nervous system: headaches and other chronic pain, infections, inflammatory and autoimmune disorders of the spinal column, seizure disorders, stroke, multiple sclerosis and neurodegenerative disorders. The latter includes Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS and Huntington’s. Most neurologists are exposed to various diseases and conditions during formal training but focus on only a few in practice. So, it’s crucial to seek a neurologist experienced in diagnosing and treating people with dementia.

Neurologists perform medical testing to determine the cause of dementia. They might order lab tests or brain-imaging scans to rule out other medical conditions, such as thyroid disorders, vitamin deficiencies, tumors or strokes. Like other medical doctors, they also can prescribe medications and therapies to bolster thinking, memory and speaking skills or help with problem behaviors.

Neuropsychologists

A neuropsychologist is a Ph.D. or Psy.D. rather than a medical doctor. They assess a patient’s cognitive skills and how brain disease, injury or mental health conditions might impact them. The neuropsychologist has patients answer questions or perform tasks to determine their memory, abstract thinking, problem-solving, language and judgment skills.

Neuropsychologists generally partner with PCPs and specialists to clarify a dementia diagnosis. According to recent studies, adding them to the team often leads to a quicker, more accurate diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or dementia. In fact, recent studies found neuropsychologists differentiate Alzheimer’s dementia from nondementia with nearly 90% accuracy.

When a loved one lives with dementia, a neuropsychologist can

- Recommend whether they should drive or live alone

- Address whether they’re capable of handling money or making legal and medical decisions

- Assess how well they respond to medications

- Determine whether they also need to be treated for depression.

Geriatric psychiatrists

Geriatric psychiatrists receive additional training in preventing, diagnosing and treating mental and emotional disorders in older adults. They create treatment plans to address seniors’ unique physical, emotional and social needs.

Your loved one’s PCP may refer you to a geriatric psychiatrist to determine whether depression or other undiagnosed mental illnesses might contribute to their memory loss. A geriatric psychiatrist could be a long-term player on your care team if your loved one suffers from problem dementia-related behaviors like extreme mood swings, outbursts or aggression.

NIH Alzheimer’s Disease Centers

We’re lucky to have one of the National Institute of Aging’s 31 NIH Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers in the Kansas City area. The University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center is best known for its groundbreaking studies and programs to train future researchers and clinicians. However, these Centers also run premier clinics for disorders like Alzheimer’s, frontotemporal dementia and Lewy Body dementia. Under the care of world-class specialists, family caregivers can find expert help diagnosing and managing complex forms of dementia.

Fitness & conditioning

Your loved one’s care team might involve allied health professionals like the following:

Physical therapist

With a doctor’s order, a physical therapist helps your loved one strengthen weak muscles and stretch stiff ones. Exercise improves balance, stability and coordination, thereby reducing fall risk. And, of course, staying active wards off heart and other diseases.

Speech therapist

A doctor also might prescribe speech therapy. Speech-language pathologists routinely address difficulties with eating, drinking and swallowing, as well as voice and speech problems. They also offer memory aids and strategies for people in the early stages of dementia.

If your loved one is having more trouble finding the right word, telling a long story or getting to the point, ask whether a speech therapist could help. When dementia caregivers communicate better, they often reduce the frustration at the root of many problem behaviors.

Occupational therapist

A prescription for occupational therapy also is a gift to the dementia caregiver. An occupational therapist looks for ways to safely maintain your loved one’s independence. They simplify tasks, then alter the environment to reduce or eliminate the need for assistance. Occupational therapy often prolongs independence or reduces the care level required.

Activities directors and recreational, art, music and massage therapists

Professionals in memory care regularly seek out alternative, non-drug interventions. They can reduce apathy, agitation and aggression; after all, physical activity has been proven to lift endorphin levels, mood, cognitive skills and overall quality of life. Look for a quality day program that offers one or all of these, giving your loved one a change of pace while you enjoy a few hours of respite.

The squad

More help for caregivers

Below is a list of other professionals caregivers frequently call on. They’re often great resources, too, pointing you to local resources that meet your and your loved one’s unique needs.

Your doctor’s support staff:

Nurses, physician’s assistants or nurse practitioners

These medical professionals are your lifelines. After all, you depend on them to get your urgent messages to the doctor. Furthermore, many are trained to answer medication questions, recognize which symptoms need a doctor’s immediate attention and walk you through difficult moments.

Social workers or case managers

Hospital social worker

If your loved one is hospitalized, then they’ll likely meet with one of the licensed social workers on staff.

- Their job is to protect your loved one’s welfare by (i) helping them cope with the emergency that landed them in the hospital and (ii) seeing they receive care that’s medically necessary but won’t overwhelm them financially (e.g., meets the requirements of their health insurance plan).

- To do so, hospital social workers evaluate patients’ mental and emotional health as well as their social or family support and financial resources.

- These social workers provide patients counseling, connect them with resources (particularly financial assistance) and arrange for equipment or services required after discharge (e.g., oxygen, durable medical equipment or a bed in a rehab facility).

Case managers

On the other hand, case managers plan, coordinate and oversee care for clients with long-term or chronic illnesses. They generally manage care.

- A case manager determines the support a patient needs, then presents and guides them through their options.

- They continue to advocate on behalf of their client, often monitoring and evaluating ongoing care.

- While not all states require case managers to be licensed, the vast majority have earned an advanced certification, such as Certified Case Manager (CCM), Accredited Case Manager (ACM), Certified Social Work Case Manager (C-SWCM) or Certified Advanced Social Work Case Manager (C-ASWCM). Most also are licensed nurses, social workers, occupational therapists or physical therapists.

Geriatric care managers

An older adult or their caregiver may hire a geriatric care manager (a specialized case manager) as their advocate and guide when navigating daily life grows challenging.

- Typically, a geriatric care manager conducts various assessments, then recommends a comprehensive long-term plan.

- Many work in private firms that serve as legal, healthcare and financial advocates. They can help clients find in-home aides — arrange placement in independent senior living, assisted living or skilled care — schedule doctor’s visits and transport — coordinate communication within the care team — handle insurance claims, bill payment, asset monitoring and tax return preparation — and advise on other healthcare, legal, financial or tax issues.

- Helpful tip: Because a geriatric care manager helps family caregivers stay focused while at work, some employee assistance programs cover part of their fees. Don’t forget to check whether your loved one’s long-term care insurance pays them, too.

Professional caregivers

As the physical and emotional demands of memory care increase, caregivers grow to appreciate the skills and support of the professional caregivers who “spell” them. That includes visiting nurses, home health aides and on-site nursing staff.

These are the letters you might see after their names (in the state of Kansas):

- RN: registered nurse

- LPN: licensed practical nurse

- CMA: certified medication aide

- CNA: certified nurse aide

- HHA: home health aide

Chaplains (help for caregivers, too!)

You might be surprised at this entry on our list. However, it’s important to consider ALL your loved one’s needs in memory care.

Our colleagues in hospice care often remind us to include spiritual support. If your loved one finds comfort in their religious traditions, consider asking a member of the clergy care team from their place of worship to visit. Many hospitals and hospices also have non-denominational chaplains on staff, trained to support people with chronic conditions.

Support groups, where caregivers help each other

The players listed above focus on your loved one’s welfare. However, your care team isn’t complete until you add someone who comforts you. You may already visit with a psychologist, social worker or spiritual advisor. If not, or if you’re looking for someone who fully appreciates your current challenges, consider joining a dementia caregivers support group to connect with those who best appreciate your daily challenges.

When it’s time for you to consider memory care assisted living, we’d be honored to join your team. We’ve been helping Kansas City caregivers keep their loved ones safe and happy since 2005. Arrange a tour to see why Kansas City’s families keep coming home to Care Haven.